The Inner Monologue: Deciphering the P91 Matrix

When I think about P91 alloy steel, I don’t just see a pipe; I see a metallurgical response to the relentless demands of supercritical power generation. It’s a material born from the necessity to move beyond the limitations of P22 and P11. Why P91? The ‘9’ is the chromium, the ‘1’ is the molybdenum. But that’s just the surface. My mind drifts to the martensitic microstructure—that dense, needle-like lattice that provides the creep strength. I’m thinking about the vanadium and niobium, those tiny micro-alloying elements that act like anchors, pinning the grain boundaries at $600^\circ\text{C}$. If those boundaries move, the pipe creeps. If it creeps, it fails. I need to explore the delicate balance of the heat treatment—the normalizing and tempering—because if the cooling rate is off by even a fraction, the martensite transforms into something brittle or too soft. It’s a high-wire act of chemistry and thermodynamics. I should also consider the welding—the “soft zone” in the Heat Affected Zone (HAZ). That’s where the nightmares of power plant engineers live. How do we quantify this? Creep-rupture strength. I need to compare P91 against its predecessors to show why it allowed for thinner walls and higher efficiency. It’s about the thermal fatigue. Thinner walls mean less thermal stress during start-up. This is a story of efficiency versus entropy.

The Metallurgical Architecture of ASTM A335 P91

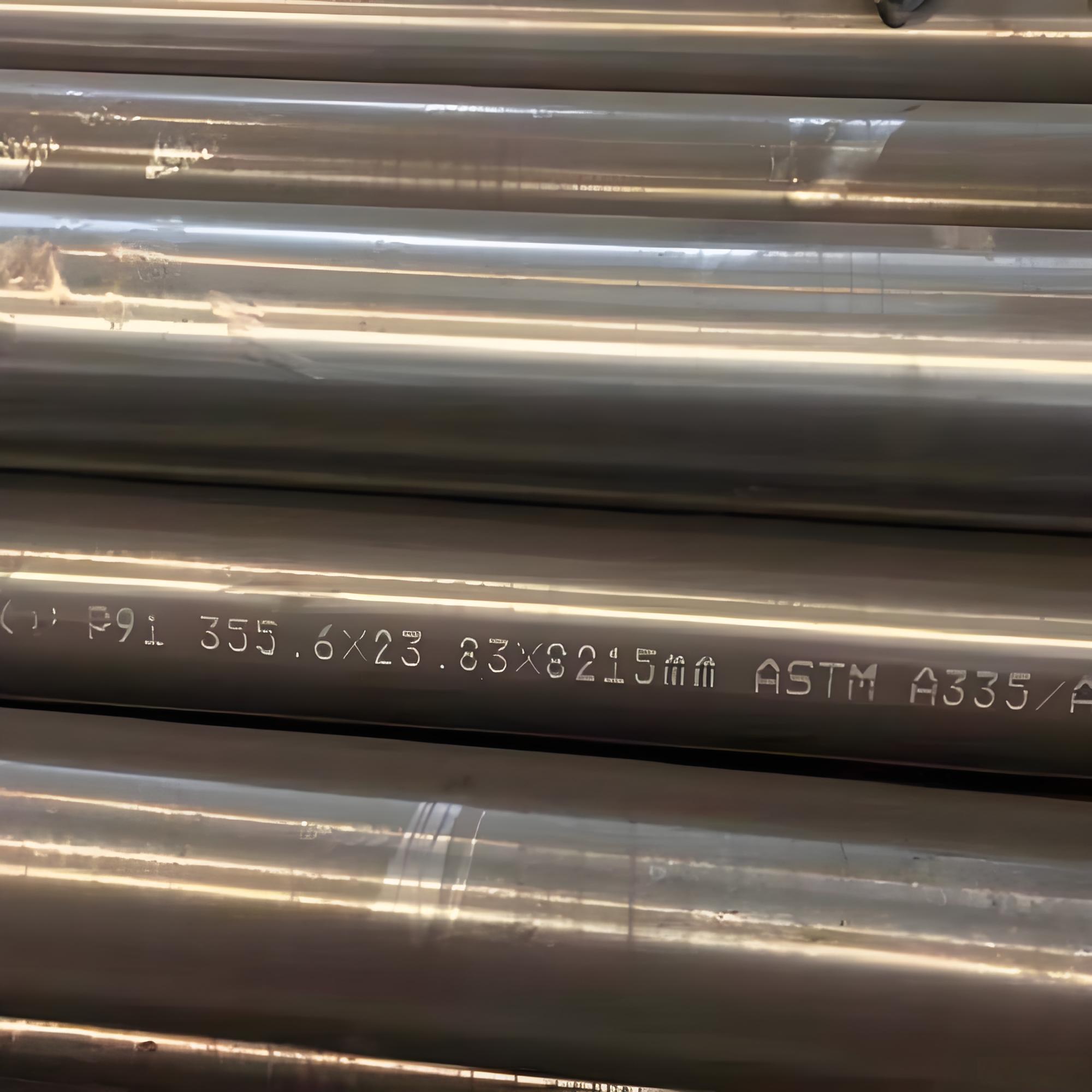

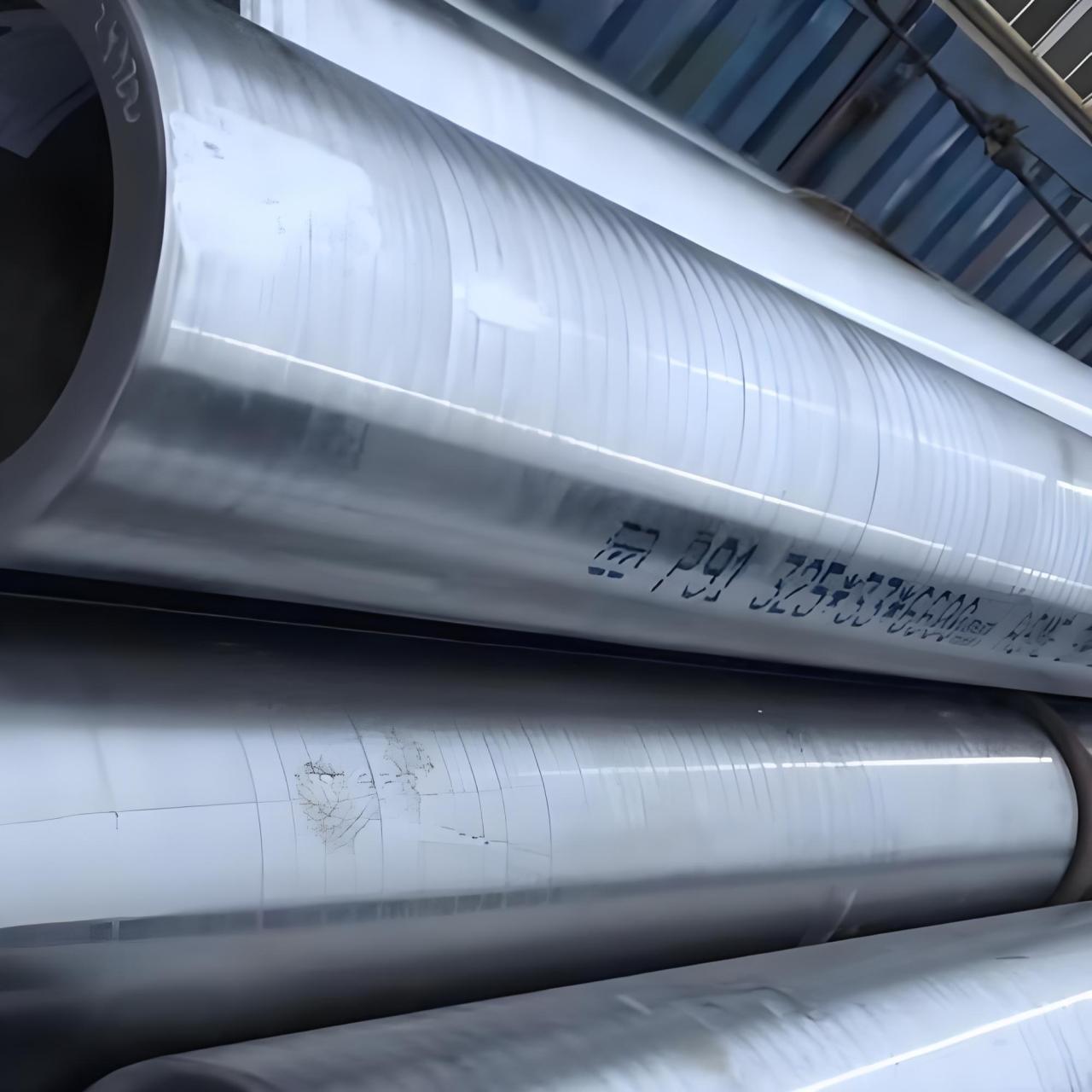

P91 alloy steel (9% Chromium, 1% Molybdenum, plus Vanadium and Niobium) is technically classified as a modified martensitic stainless steel, though in the industry, we call it a high-alloy ferritic steel. Its introduction revolutionized the design of headers and main steam piping in ultra-supercritical (USC) plants. The primary challenge in these environments is not just pressure—it is the simultaneous presence of high temperature and time, a combination that leads to “creep.”

The Chemistry of Sustained Strength

The superiority of P91 over traditional low-alloy steels like P22 lies in its complex chemistry. Each element serves a specific structural purpose. Chromium provides the oxidation resistance necessary for steam environments. In the $550^\circ\text{C}$ to $620^\circ\text{C}$ range, steam becomes highly corrosive. The 9% Cr content forms a stable protective oxide layer.

However, the real magic happens with the micro-additions. Vanadium (V) and Niobium (Nb) form fine carbonitrides (V, Nb)(C, N). These precipitates are dispersed throughout the matrix. Imagine a sponge filled with tiny, hard diamonds; these diamonds prevent the sponge from deforming under pressure. In metallurgical terms, these precipitates impede dislocation movement. Without them, the steel would “flow” over time under the weight of the steam pressure.

| Element | Weight % (P91) | Functional Role |

| Chromium (Cr) | 8.00 – 9.50 | Oxidation resistance & Ferrite stabilization |

| Molybdenum (Mo) | 0.85 – 1.05 | Solid solution strengthening; Creep resistance |

| Vanadium (V) | 0.18 – 0.25 | Hard carbide formation; Grain refinement |

| Niobium (Nb) | 0.06 – 0.10 | Carbonitride precipitation; Creep-rupture life |

| Nitrogen (N) | 0.03 – 0.07 | Strengthening through interstitial hardening |

| Carbon (C) | 0.08 – 0.12 | Martensite formation and carbide precursor |

Thermodynamic Stability: The Martensitic Advantage

Traditional P22 steel has a ferritic-pearlitic microstructure. While stable at lower temperatures, pearlite begins to spheroidize and weaken as it approaches $540^\circ\text{C}$. P91 is designed to stay in a tempered martensitic state.

During the manufacturing process, the seamless pipe is normalized at approximately $1040^\circ\text{C}$ to $1080^\circ\text{C}$, transforming the structure into austenite. It is then air-cooled to form fresh martensite. The subsequent tempering (usually between $730^\circ\text{C}$ and $780^\circ\text{C}$) is the most critical phase. This tempering reduces the internal stresses and allows for the precipitation of $M_{23}C_6$ carbides at the grain boundaries.

The result is a material that maintains a high yield strength even as temperatures climb. This high strength-to-weight ratio allows engineers to design pipes with significantly thinner walls than would be required for P22.

The “Thin-Wall” Ripple Effect

-

Reduced Weight: Thinner pipes mean less load on the structural steel of the boiler.

-

Thermal Fatigue Resistance: Thick-walled pipes suffer from a temperature gradient between the inner and outer skin. During a rapid start-up, the inner skin expands faster than the outer skin, leading to cracks. P91’s thinner walls equalize temperature faster, allowing for more flexible plant operations (cycling).

-

Improved Heat Transfer: Less mass means less heat is lost to the piping itself, improving the overall cycle efficiency.

Mechanical Properties and Creep Rupture

The design life of a power plant is typically 200,000 hours. P91 is evaluated based on its “Creep Rupture Strength”—the stress at which the material will fail after 100,000 or 200,000 hours at a specific temperature.

Compared to P22, P91 offers nearly double the allowable stress at $570^\circ\text{C}$. This is why P91 became the industry standard for “Main Steam” and “Hot Reheat” piping.

| Property | P22 Steel (at 550°C) | P91 Steel (at 550°C) |

| Tensile Strength (MPa) | ~415 | ~585 |

| Yield Strength (MPa) | ~205 | ~415 |

| Allowable Stress (ASME) | ~45 MPa | ~100 MPa |

| Thermal Conductivity | 26 W/m-K | 28 W/m-K |

| Max Service Temp | 565°C | 620°C |

The Achilles Heel: Fabrication and Welding

The very complexity that makes P91 superior also makes it incredibly sensitive to human error during installation. Welding P91 is not like welding carbon steel. It requires a strict regimen of Pre-heat, Inter-pass temperature control, and Post-Weld Heat Treatment (PWHT).

The Heat Affected Zone (HAZ) of a P91 weld is the most vulnerable point. During welding, a small region of the parent metal is heated to just below the transformation temperature. This creates a “Type IV” soft zone. If the PWHT is not performed correctly—if the temperature is too low or the hold time is too short—this soft zone becomes the site of premature creep failure. Many catastrophic failures in the mid-2000s were traced back to improper PWHT, where the carbides over-coarsened, leaving the grain boundaries weak.

Critical Welding Parameters:

-

Preheat: $200^\circ\text{C}$ to $250^\circ\text{C}$ to prevent hydrogen cracking in the martensite.

-

Hydrogen Control: Use of low-hydrogen electrodes is mandatory.

-

PWHT: $750^\circ\text{C}$ ($\pm 10^\circ\text{C}$) for at least 2 hours (depending on thickness). Deviating by even $20^\circ\text{C}$ can result in a 50% reduction in creep life.

The Inner Monologue: The Micro-Temporal Battle

I’m digging deeper now. I can’t stop at just the chemistry; I have to inhabit the lattice. I’m thinking about the “Type IV” cracking phenomenon—the silent killer of P91. It’s not a sudden snap; it’s a microscopic void formation at the boundary between the fine-grained heat-affected zone and the unaffected parent metal. Why there? Because that specific sliver of steel reached a temperature during welding that was just enough to dissolve the precipitates but not enough to reform the martensite properly. It’s a “zone of weakness” only a few millimeters wide. I need to think about the Laves phase—those intermetallic brittle clusters that grow over 50,000 hours. They steal the Molybdenum from the matrix, leaving the steel “starved” of solid solution strengthening. If I’m an engineer in a plant, how do I see this? I can’t see it with the naked eye. I have to use surface replication—cellulose acetate film to “fingerprint” the grain structure. And then there’s the steam-side oxidation. The internal scale. If it gets too thick, it acts as an insulator, the tube metal temperature (TMT) rises, and the creep rate doubles for every $10^\circ\text{C}$ increase. This is a feedback loop of destruction. I need to explain the “creep-fatigue interaction”—how the cycling of modern plants (turning them on and off daily) interacts with the constant pressure of the steam. This is where P91 either proves its worth or reveals its fragility.

Part II: Deep-Dive into Degradation and Lifecycle Management

To understand P91 at an expert level, we must move beyond the “as-manufactured” state and look at the “aged” state. After 100,000 hours at $580^\circ\text{C}$ and $18\text{ MPa}$, P91 is a different material than the one that left the mill.

The Phenomenon of Creep-Rupture and the “Soft Zone”

The most significant technical challenge with P91 is its localized vulnerability during the welding process. When we weld two sections of P91 pipe, we create a thermal gradient.

-

Fusion Zone: The weld metal itself.

-

CGHAZ (Coarse-Grained Heat Affected Zone): Heated to very high temperatures, forming large grains.

-

FGHAZ (Fine-Grained Heat Affected Zone): Heated just above the $Ac_3$ transformation temperature.

-

ICHAZ (Inter-Critical Heat Affected Zone): The “Soft Zone.”

The ICHAZ is where the $Ac_1$ temperature is reached. Here, the meticulously engineered martensitic structure is partially tempered or “over-tempered.” The (V, Nb) carbonitrides—the “anchors” we discussed earlier—begin to coarsen. Instead of a million tiny anchors, you get a thousand large ones. The distance between them increases, allowing dislocations to glide through the crystal lattice more easily.

This leads to Type IV Cracking. Under the hoop stress of the internal steam and the longitudinal stress of the piping system, voids begin to form around these coarsened carbides. These voids coalesce into micro-cracks, and eventually, the pipe fails “plastically” in a very narrow band.

| Failure Type | Location | Cause |

| Type I & II | Weld Metal | Incorrect filler metal or hydrogen cracking |

| Type III | CGHAZ | Stress relief cracking (rare in P91) |

| Type IV | ICHAZ / Base Metal Interface | Creep-void coalescence in the over-tempered zone |

Thermal Fatigue and the Cycling Reality

In the 20th century, power plants were “base-loaded”—they stayed on for months. Today, with the integration of renewables, thermal plants must “cycle” (load-following). This introduces Thermal Fatigue.

P91 is superior here because of its lower coefficient of thermal expansion and higher thermal conductivity compared to austenitic stainless steels. However, every time the steam temperature swings, the inner wall of the pipe expands or contracts faster than the outer wall.

Where:

-

$E$ = Young’s Modulus

-

$\alpha$ = Coefficient of thermal expansion

-

$\Delta T$ = Temperature gradient across the pipe wall

-

$\nu$ = Poisson’s ratio

Because P91 allows for thinner walls (due to high allowable stress), the $\Delta T$ is minimized. A P22 pipe might require a $100\text{ mm}$ wall thickness for a specific header, whereas P91 might only need $60\text{ mm}$. This $40\text{ mm}$ difference dramatically reduces the thermal stress during ramp-up, allowing the plant to reach full load faster without “consuming” its fatigue life.

Steam-Side Oxidation and the “Exfoliation” Risk

At temperatures above $565^\circ\text{C}$, a chemical reaction occurs between the steam ($H_2O$) and the Iron ($Fe$) in the pipe:

This forms a magnetite scale. In P91, the 9% Chromium helps form a (Fe,Cr)-spinel layer which is more stable than pure magnetite. However, over time, this scale grows.

The Double-Edged Sword of Scale:

-

Insulation: Magnetite has very low thermal conductivity. A $0.5\text{ mm}$ layer of scale can increase the metal temperature by $20^\circ\text{C}$ to $30^\circ\text{C}$ because the heat from the flue gas cannot transfer into the steam efficiently.

-

Exfoliation: During a shutdown, the steel pipe contracts faster than the brittle oxide scale. The scale flakes off (exfoliates) and is carried by the steam at high velocities into the steam turbine. This causes Solid Particle Erosion (SPE) on the turbine blades, leading to millions of dollars in efficiency losses and repair costs.

Non-Destructive Evaluation (NDE) and Replication

How do we know if a P91 pipe is dying? Traditional Ultrasonic Testing (UT) can find a crack, but by the time there is a crack, it’s often too late. We use In-situ Metallography (Replication).

Engineers polish a small area of the pipe to a mirror finish and etch it with a weak acid (Nital). They then apply a cellulose acetate film to take a “negative” of the microstructure. Under a scanning electron microscope (SEM), we look for:

-

Carbide Coarsening: Are the $M_{23}C_6$ precipitates getting too big?

-

Laves Phase: Presence of $Fe_2(Mo, W)$ clusters.

-

Void Density: The number of creep voids per square millimeter (Neubauer Classification).

| Creep Stage | Microstructural Observation | Action Required |

| Stage A | Isolated Voids | Normal monitoring (3-5 years) |

| Stage B | Oriented Voids | Increased monitoring (1-2 years) |

| Stage C | Micro-cracks (Linked voids) | Repair or replace within 6 months |

| Stage D | Macro-cracks | Immediate Shutdown |

The Economic Argument for P91

While the raw material cost of P91 is roughly 2 to 3 times that of P22, the System Level Cost is often lower:

-

Lower Hanger Loads: Because the piping is 30-40% lighter, the support structures and constant-load hangers are smaller and cheaper.

-

Welding Volume: A thinner wall requires fewer “passes” with the welding torch. Even though the hourly rate for a P91-qualified welder is higher, the total man-hours are reduced.

-

Life Extension: The resistance to thermal fatigue allows for a “flexible” operation mode that is essential in the modern energy market.

Final Technical Summary

P91 is not just a steel; it is a complex, metastable chemical system. Its performance is entirely dependent on the preservation of its martensitic microstructure.

-

Precision in Chemistry: The V and Nb content must be tightly controlled to ensure carbonitride precipitation.

-

Precision in Heat Treatment: The tempering temperature is the “DNA” of the pipe’s future performance.

-

Precision in Fabrication: Welding and PWHT are the most likely points of failure.

In an era where efficiency and carbon reduction are paramount, P91 enables the higher steam temperatures required for advanced thermal cycles. It remains the backbone of modern high-temperature piping engineering, provided it is treated with the metallurgical respect its complexity demands.

Conclusion: The Future of Alloy Design

P91 was the bridge to the future. It paved the way for P92 (which adds Tungsten) and P122. However, P91 remains the “sweet spot” of the industry—balancing cost, availability, and performance. For high-pressure, high-temperature service, its ability to maintain structural integrity through precipitation hardening makes it an indispensable asset in modern thermal dynamics.

The transition from P22 to P91 wasn’t just a material swap; it was an engineering shift toward precision. Understanding the phase transformations and the delicate interplay of Nitrides and Carbides is the only way to ensure these systems operate safely for their intended 30-year lifespans.

You must be logged in to post a comment.